Edvard Munch stands as one of the most influential figures in modern art history, whose distinctive style and psychological depth transformed artistic expression in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While “The Scream” remains his most recognizable masterpiece, Munch’s body of work represents a profound exploration of human anxiety, alienation, and emotional turmoil that continues to resonate with audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on December 12, 1863, in Løten, Norway, Munch’s childhood was marked by tragedy. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was just five years old, and his sister Sophie succumbed to the same disease nine years later. These early encounters with death and grief profoundly shaped his worldview and would become recurring themes in his artistic expression.

Munch’s father, a military physician, was deeply religious and instilled in his children a sense of piety tinged with the fear of damnation. This strict religious upbringing, combined with his experiences of loss, contributed to Munch’s preoccupation with mortality and existential dread that would later define his artistic vision.

Despite his father’s disapproval, Munch enrolled at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania (now Oslo) in 1881. His early training was conventional, but he soon broke away from academic traditions after being influenced by naturalism and impressionism during his travels to Paris in the 1880s.

Artistic Development and the “Frieze of Life”

Munch’s distinctive style emerged in the 1890s as he began to move away from impressionism toward a more symbolic and emotionally charged approach. His work during this period was characterized by simplified forms, bold outlines, and undulating lines that conveyed psychological states rather than physical reality.

In 1893, Munch began what would become his most significant body of work, the “Frieze of Life,” a series of paintings that explored themes of life, love, anxiety, and death. This ambitious cycle included some of his most famous works, including “The Scream,” “Anxiety,” “Madonna,” and “The Dance of Life.” Through these interconnected paintings, Munch sought to create a comprehensive visual exploration of the human psyche and the journey through life’s emotional landscapes.

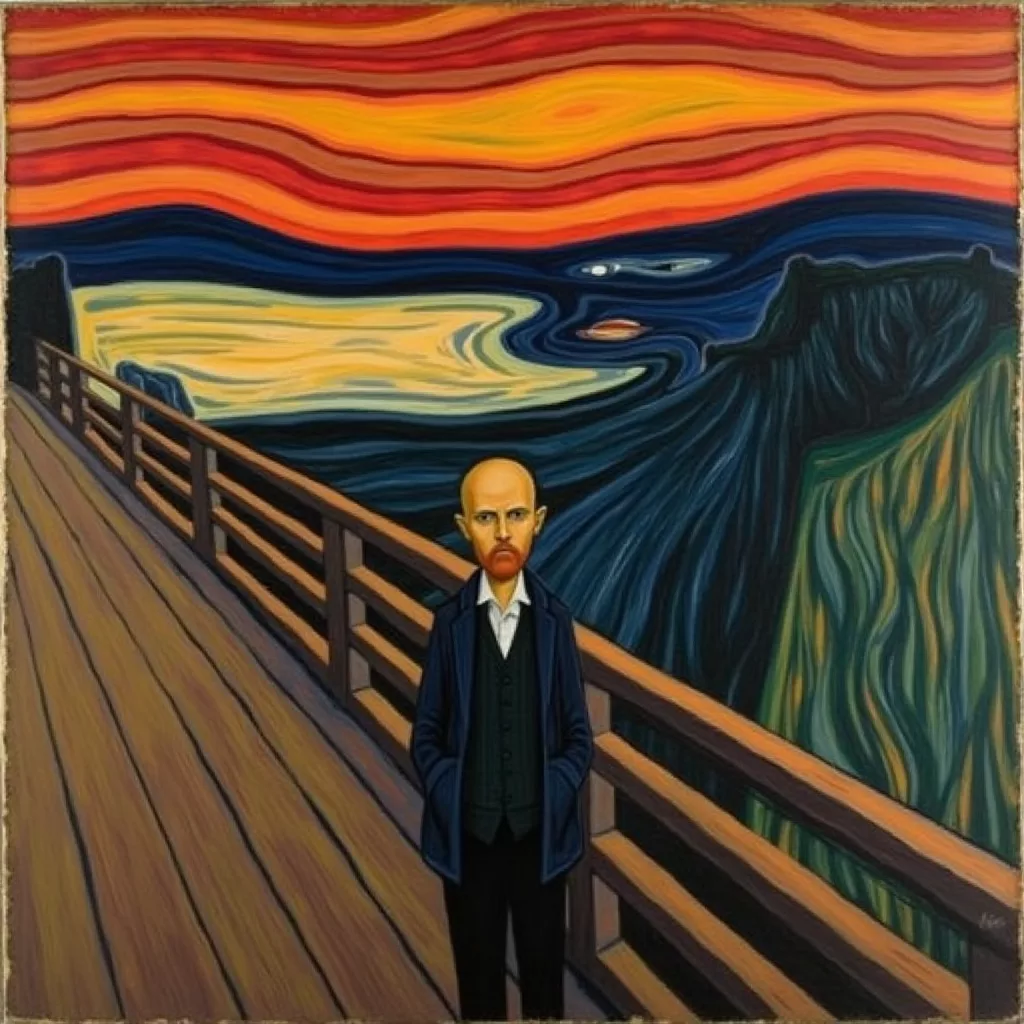

“The Scream”: A Universal Icon of Existential Anxiety

“The Scream” (1893) stands not only as Munch’s magnum opus but as one of the most recognizable images in Western art. The painting depicts a figure with an agonized expression against a landscape with a tumultuous orange sky. Munch created multiple versions of “The Scream” between 1893 and 1910, using various media including paint, pastel, and lithography.

The genesis of this powerful image came from Munch’s own experience, which he described in his diary:

“I was walking along the road with two friends—the sun was setting—suddenly the sky turned blood red—I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence—there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city—my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety—and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

What makes “The Scream” so enduringly powerful is its ability to visualize internal psychological states. The distorted figure, with its skull-like face and hands clasped to its cheeks, has become a universal symbol of anxiety and alienation in the modern world. The swirling landscape seems to vibrate with the figure’s emotional distress, blurring the boundary between internal experience and external reality.

Art historians interpret “The Scream” as a pivotal work that bridges 19th-century Symbolism and 20th-century Expressionism. Its distortions of form for emotional effect anticipated the work of later expressionists and even aspects of abstract art. The painting’s influence extends far beyond the art world, permeating popular culture through countless references, parodies, and adaptations.

Psychological Themes and Innovative Techniques

Munch’s art is distinguished by its focus on psychological themes that were often considered taboo in his time. He explored sexuality, illness, jealousy, and mental anguish with unprecedented directness. His painting “Puberty” (1894-95) depicts the anxiety of adolescence, while “Death in the Sickroom” (1893) revisits the trauma of his sister’s death.

Technically, Munch was an innovator who experimented with various media and techniques. He developed a distinctive style characterized by:

- Bold, simplified forms that emphasized emotional impact over realistic detail

- Unconventional perspectives and spatial distortions that enhanced psychological tension

- Vibrant, sometimes jarring color combinations that conveyed emotional states

- Rhythmic, flowing lines that unified his compositions and suggested movement

- Experimental printing techniques that expanded the expressive possibilities of woodcuts and lithography

Munch was also one of the first artists to embrace photography not merely as a documentary tool but as an artistic medium in its own right. His photographic self-portraits reveal the same interest in psychological exploration evident in his paintings.

The “Munch Museum” Period and Legacy

After suffering a nervous breakdown in 1908, Munch underwent therapy and his art gradually became more colorful and less anxiety-ridden. In 1916, he purchased a property at Ekely, near Oslo, where he would live in relative isolation until his death. During these later years, he focused increasingly on landscapes, self-portraits, and scenes of rural life, though still imbued with his characteristic psychological intensity.

When Norway was occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II, Munch lived in fear that his art, which the Nazi regime had labeled “degenerate,” would be confiscated. He died on January 23, 1944, at the age of 80, leaving behind approximately 1,100 paintings, 4,500 drawings, and 18,000 prints. In his will, he bequeathed his remaining works to the city of Oslo, which later established the Munch Museum to house this extraordinary collection.

Munch’s influence on 20th-century art cannot be overstated. His emotional intensity and psychological exploration paved the way for German Expressionism, particularly the work of artists in Die Brücke group. His use of color and form as vehicles for emotional expression influenced Fauvism and early Abstract Expressionism. Contemporary artists continue to find inspiration in his unflinching examination of the human condition.

Critical Reception and Artistic Position

During his lifetime, Munch’s work often provoked controversy. His first major exhibition in Berlin in 1892 caused such a scandal that it was closed after just one week. Critics were disturbed by the emotional intensity and perceived morbidity of his images, as well as their departure from conventional aesthetic standards.

However, Munch gradually gained recognition, particularly in Germany, where his psychological approach resonated with emerging expressionist tendencies. By the time of his death, he was recognized in Norway as a national treasure, though full international appreciation of his significance would come largely after World War II.

Munch occupies a unique position in art history, standing at the crossroads between 19th-century Symbolism and 20th-century Expressionism. While often grouped with post-impressionists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, with whom he shares an interest in emotional expression through color and form, Munch’s systematic exploration of psychological states anticipates later movements like Surrealism and Existential art.

Munch’s Artistic Philosophy

Munch articulated his artistic philosophy in various writings and statements throughout his career. He rejected the notion of art as mere representation, instead viewing it as a means of expressing profound emotional and existential truths. “I do not paint what I see,” he declared, “but what I saw,” suggesting that his art was concerned with memory and emotional imprints rather than visual appearances.

For Munch, art was inseparable from life experience: “My art is rooted in a single reflection: why am I not as others are? Why was there a curse on my cradle? Why did I come into the world without a choice, why…?” This questioning, searching quality permeates his work, making it deeply personal yet universally resonant.

He believed in the communicative power of art to transcend individual experience: “From my rotting body, flowers shall grow, and I am in them, and that is eternity.” This statement reflects Munch’s complex relationship with mortality and his belief in art’s capacity to achieve a form of immortality.

Contemporary Relevance and Cultural Impact

More than a century after its creation, “The Scream” remains extraordinarily relevant in our anxiety-ridden age. Its evocation of existential dread speaks to contemporary concerns about environmental crisis, social alienation, and psychological fragility. The image has become a visual shorthand for modern anxiety, appropriated and referenced in countless contexts from political cartoons to emoji.

The record-breaking sales of Munch’s works at auction—a pastel version of “The Scream” sold for $119.9 million in 2012—attest to his enduring market value. But beyond monetary worth, Munch’s true significance lies in his pioneering exploration of the human psyche through visual art.

In an era of increasing awareness of mental health issues, Munch’s unflinching depictions of psychological states take on renewed significance. His work reminds us that art can function not merely as decoration or entertainment but as a profound exploration of what it means to be human in all its complexity—its joy and sorrow, connection and alienation, vitality and mortality.

Conclusion

Edvard Munch transformed modern art by bringing unprecedented psychological depth and emotional intensity to visual expression. Through works like “The Scream,” he created a new visual language capable of conveying the complexities of human experience in an industrializing world undergoing rapid social and intellectual change.

What distinguishes Munch is not merely his technical innovations or his pivotal historical position, but his unwavering commitment to exploring the depths of human experience. In his unflinching examinations of anxiety, love, jealousy, and death, he created a body of work that continues to speak powerfully to successive generations, transcending cultural and temporal boundaries.

Art11deco